My first publication: Quantum Immortality

Notes on a paper accepted to Synthese

Encouraged by my friend Philip Goff, I’ve recently made a bit of an effort to publish something in a philosophy journal. Why? I’m not sure. I’m not an academic, so there’s no real incentive from a career point of view. But it’s an interesting challenge, and a way to prove to myself that perhaps I’m not a crank.

I found it to be an enjoyable and challenging process, so not that bad as a hobby. Especially now that I’ve had my first acceptance, from Synthese, on a paper outlining my perspective on the idea of quantum immortality (free preprint here, paywalled official version here).

Quantum immortality is, on the face of it, a dumb idea. The red-headed step-child (with apologies to any red-headed step-children reading this) of the Many Worlds Interpretation of quantum mechanics. No Everettian wants it to be true, and so it is often dismissed. The problem is that, as far as I can see, none of the arguments against it hold water. In this paper, I tackle arguments against quantum immortality from David Papineau, David Wallace and Sean Carroll and aim to show that their position is inconsistent.

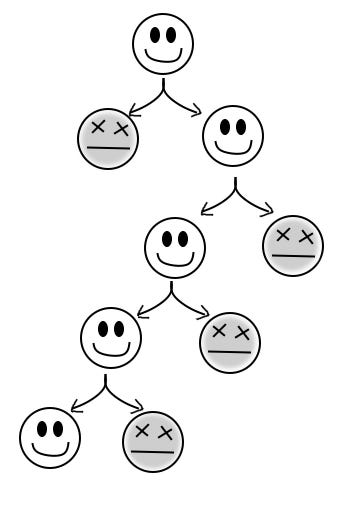

The idea of quantum immortality arises when thinking through some of the consequences of Everettian quantum mechanics, where every quantum measurement splits the world, including you. This is often illustrated with the example of Schrödinger’s cat, where just such a measurement results in a cat either living or dying. You either find yourself on a branch where the cat is alive or where it is dead. But what if you’re the cat? The suggestion of quantum immortality is that the cat should always expect to survive, because a dead cat makes no observations.

This can be thought of in terms of a quantum suicide thought experiment, where you play a game of quantum Russian roulette with a gun which kills you instantly if it measures spin-up on an appropriately prepared electron—a quantum coin-flip. If you keep repeating this experiment, then, from an objective point of view, you would not expect to survive very long. But if quantum immortality is right, then, from your own point of view, you will always survive.

In the paper, I look at two questions we might want to ask regarding quantum immortality. First, suppose that I engage in such a repeated quantum suicide experiment, and find that I survive after many rounds. If we rule out the idea that the apparatus is not working as expected, does my unlikely survival provide me with evidence that Everettian quantum mechanics is right? And second, does it give me reason to believe that my luck will continue, because of quantum immortality?

David Papineau takes on the first question, of whether quantum immortality can provide evidence of the many worlds interpretation, and says that it cannot. I draw a parallel between the argument he presents and Roger White’s argument that the fine-tuning of the constants cannot provide evidence for a cosmological multiverse. This is interesting because White’s argument is not likely to be readily accepted by Everettians, for various reason. Both arguments work by pointing out that the hypothesis that there are many other instances in the multiverse where things work out differently doesn’t explain why things have worked out so suspiciously to your advantage in this universe. Specifically, for Papineau, that the many worlds interpretation is true doesn’t make it any more likely that this specific copy of you would survive, and so it is just as much a freak coincidence as if the many worlds interpretation were not true.

My argument against this is detailed and technical, but it boils down to this: the only way to make sense of the idea that things could have gone otherwise is if we posit a mysterious sense of personal identity, or haecceity, to differentiate the different versions of you, allowing us to track which is which irrespective of their qualities. For example, if we label two versions of you as you-alpha and you-beta, maybe you-alpha dies and you-beta survives, and then you-beta considers themselves lucky it turned out this way.

But without such a posit, all we have left are the qualitative differences. There’s the dead you, and the surviving you, and that’s all there is to it. It is a tautology that the surviving you survives, so it is not surprising. Conversely, if you’re not duplicating all the time, then it is surprising that there should be a surviving you at all. This is why I think that survival is evidence for many worlds.

So it would seem that it’s up in the air, depending on whether we accept haecceities (or something like them). The problem for the targets of my paper—Papineau, Carroll and Wallace—is that they are all on record as being against haecceities. And for good reason! Everettianism is for them motivated by parsimony, as the picture that emerges if we accept the unitary evolution of the wavefunction and discard unnecessary complications such as collapse postulates or hidden variables. Haecceities are just the sort of unnecessary complication that Everettians typically prefer to do without. As such, while Papineau’s view here is defensible, it comes with a cost he may not be willing to pay.

For the other question, about whether you should expect to survive, all three of my targets have been dismissive. There’s a lot to address here, but I suppose the easiest way of summing up the general attitude is to note that the Born rule is what we use to make predictions in quantum mechanics, and the Born rule says you should expect to die with overwhelming probability in a repeated quantum suicide experiment. For my targets, there is no motivation to deviate from the Born rule, and so quantum immortality is silly.

The Born rule tells us what we should expect to happen. But, as I argue in the paper, there is another question we could ask: what should you expect to experience? If death cannot be experienced, then the Born rule cannot be telling us what to expect to experience in cases of quantum suicide, because the Born rule will assign a high probability to an outcome that cannot be experienced. If many worlds is not true, we might, I suppose, expect experience to end. But if many worlds is true, then there is always some branch where experience continues, and so we cannot expect experience to end. Even if experience ends on a particular branch, all three of my targets seem to follow Parfit’s view that what matters for survival is psychological continuity and not physical continuity in a particular location. Only in many worlds are we guaranteed that somewhere in the multiverse there will always be a psychological successor, so that we should expect to experience immortality.

If there are two versions of the question of what to expect—what to expect to happen versus what to expect to experience—then it seems we are at an impasse. But then we are faced with a meta-question: which is the right question to ask? Which question should I really care about? To me, this looks like a Humean is/ought problem. If reason is the slave of the passions, then these look like alternative passions, not a question reason can mediate. Different agents might want to ask different questions. We can rule out quantum immortality as irrational only by adopting some incompatible axiom of rationality, such as that rational agents must care only about what will happen in all branches, and not only about what will happen in branches they experience. But this sort of ad hoc move again runs counter to the parsimonious spirit of the Everettianism promoted by the targets of the paper.

I close out my argument by sketching a science-fictional scenario designed to pump our intuitions towards quantum immortality. I won’t recapitulate the scenario here, but you can find it in the preprint starting 2/3 of the way down page 17. If this scenario does what it’s supposed to do , then in these circumstances it will seem to you that it only makes sense to care about what will be experienced, and not about what will happen from a more objective point of view. At least, that is how the scenario strikes me—your mileage may vary. But if you agree, then there is at least one case where quantum immortality seems to be the right way to think about survival. And if there is at least one such scenario, then perhaps quantum immortality is an idea Everettians should be taking more seriously in general.

As I said, quantum immortality is not something Everettians want to be true. Not only is it counter-intuitive and absurd, it’s not good news, really. On the worst interpretation, it means that subjective death is impossible not only in idealised quantum suicide experiments but in general, because everything that happens at a macroscopic scale ultimately supervenes on microscopic quantum events that can play out in many ways. In that case, we are each condemned to live forever, long after we have tired of life, ultimately in a world where everything and everyone we love has passed away. I’m not looking forward to ending up as essentially a Boltzmann brain eking out a miserable eternal existence in the heat death epoch. As an Everettian myself, I want there to be good arguments against quantum immortality. But the arguments presented so far are not good.

Interesting post!

There is a short story you might like called The Roulette Player by Mircea Cărtărescu which describes a man who plays Russian Roulette multiple times surviving each turn. He eventually moves to games involving two, three, four, five and (absurdly) six bullets in the chamber. When he pulls the trigger on the six-bullet game an earthquake strikes and causes the bullet to miss him.

The narrator concludes that he must be inside a fictional story because nothing else explains such an improbable sequence occurring.

Link here if you’re interested: https://static10.labirint.ru/books/969389/demo.pdf

Congrats on the publication! I stumbled across the concept of ‘quantum torment’ recently and I think it’s the scariest idea I’ve ever heard.