The Ontological Argument vs Prime Numbers

Identifying exactly why the ontological arugment doesn't work.

In this post, I’m going to use a facetious point about prime numbers to explain what exactly I think is wrong with the famous Ontological Argument.

Quick recap first. Very quickly, the Ontological Argument, first proposed by St. Anselm, and then tinkered with by numerous philosophers including Descartes, Gödel and Plantinga, goes approximately as follows: God is definitionally the greatest conceivable being, having all great-making properties. It is greater to exist than not to exist, therefore existence is a great-making property and God must exist.

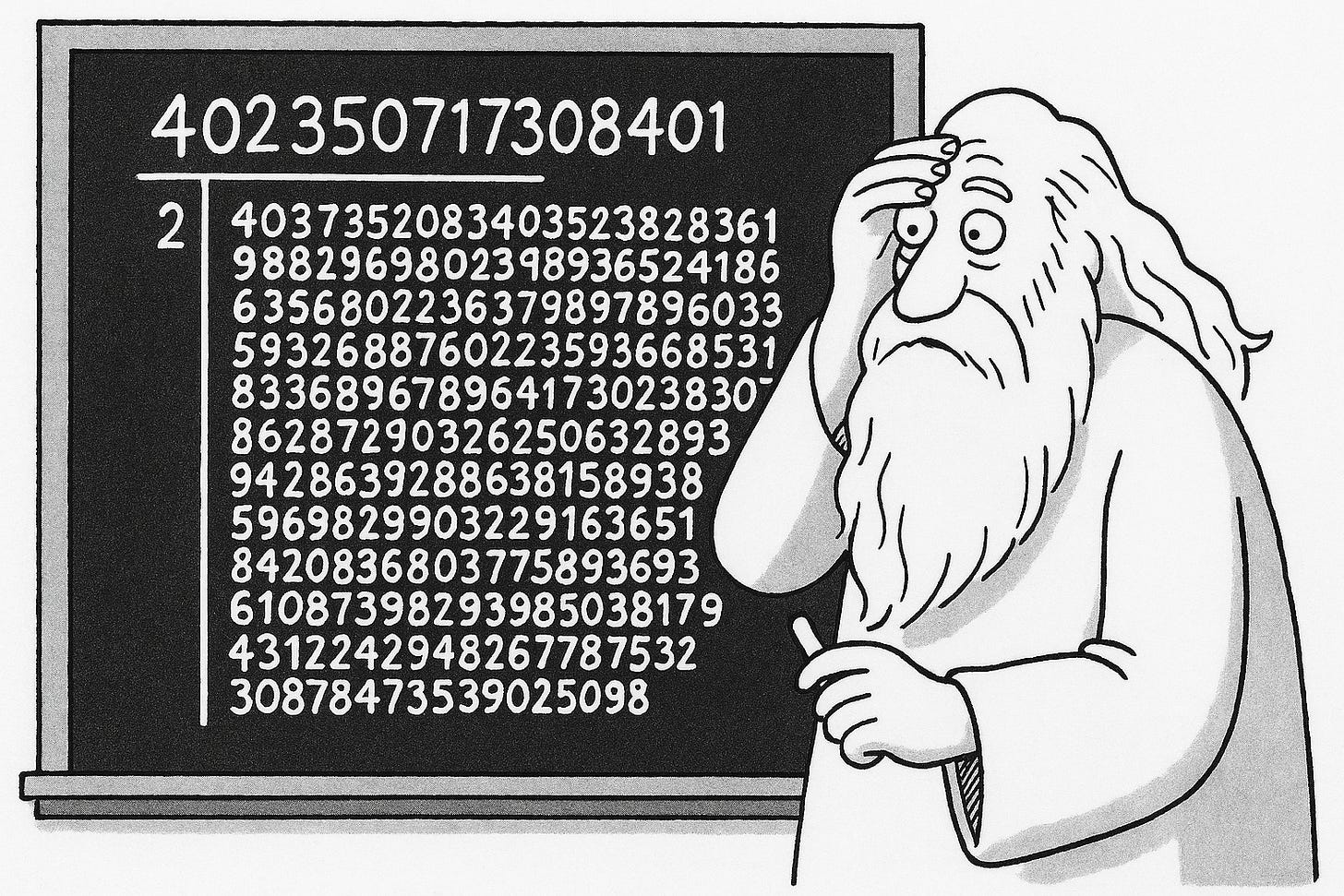

OK, let’s parallel this with my silly point about prime numbers. It really is dumb, but bear with me.

It is greater to be able to factorise a number than not to be able to factorise a number. Therefore God can factorise numbers. And it is greater to be able to factorise all numbers than to be able to factorise only some numbers. So, God can factorise all numbers. So, all numbers can be factorised, therefore prime numbers do not exist.

This argument makes no sense. There are probably a number of ways we could analyse what has gone wrong with it. Here’s one.

God is only supposed to have all the great-making properties that it is logically possible to have, and not any incoherent or logically impossible properties. This goes back to issues about omnipotence: God cannot make a rock so large he cannot lift it, because this is logically impossible for an omnipotent being. This is not really a limit to His omnipotence.

Similarly, being able to factorise all numbers is not a property that it is logically possible to have. As before, this is not really a limit to God’s perfection or omnipotence or omniscience. For my purposes, there’s a particular way I want to phrase the reason why: it is not logically possible for God to be able to factorise all numbers because numbers which are not factorisable by God are logically possible.

Now, to bring it back to the Ontological Argument itself. The key thing to realise is that the Ontological Argument, as an a priori argument, ostensibly proves not only that God exists but that God exists necessarily. That is, in all logically possible worlds, God must exist.

Here’s the parallel to my silly prime number story. I claim that there are logically possible worlds without God, just as there are logically possible numbers which cannot be factorised by God. If so, it is not logically possible for God to exist in all possible worlds, therefore God cannot exist necessarily, therefore the Ontological Argument fails to prove that God exists in this world.

I may seem to be begging the question in my claim above. The Ontological Argument purports to prove that there are no logically possible worlds without God, so it seems suspect to just claim the contrary. But here again I think it is helpful to think about prime numbers. We’ve got an argument that purports to show that prime numbers don’t exist, but by the axioms of standard mathematics they exist just fine. I think there will be wide agreement that it is the former argument that looks specious. Numbers are abstract objects that exist only relative to certain axioms, and relative to those axioms, the existence of prime numbers is logically necessary. It is not begging the question to assume those axioms. Rather, it’s the ontological argument against prime numbers that is at fault.

I think possible worlds are like that. As long as a purportedly possible world contains no internal contradictions, then that world seems to be possible. If the Ontological Argument disagrees, then it’s the Ontological Argument that’s at fault, just as is the case with prime numbers.

We’re left with this point of contention: I claim that it is not logically possible for God to exist in all possible worlds, and the Ontological Argument implicitly claims that it is. The rationale for my side is just that it seems to be possible to define a possible world without God, e.g. the world as atheists see it, or even a toy world like Conway’s Game of Life. The rationale for the other side is unstated. It needs to be established for the Ontological Argument to do its work.

A subtle point remains. I think many theists might object that God is not merely a part of the world. That God exists outside space and time. God might be seen as existing in an entirely different way than objects in the world, perhaps not unlike other necessary objects such as numbers.

But this is not what theists mean when they claim that God exists. God is not an abstract object. God is supposed to be the creator of the universe. To listen to prayers. To have incarnated as Jesus Christ. And so on. In other words, God is (or was, in the case of deism), in causal contact with the world. This makes God a part of the world on possible world semantics. A God that does not and has never interacted with the physical world might as well be in an entirely different universe or be abstract altogther. Sure, if modal realism is true, then there are certainly worlds where God exists, and so God does exist. Many different instances of God, in fact! But without some sort of interaction He would not be part of our world nor exist from our point of view any more than unicorns or leprechauns do.

Just to close, I want to point out that similar issues were noted by Hume and Kant. Hume argued that existence is not a quality or a perfection. Kant said that it wasn’t a predicate. I think I’m basically making the same point, but I think the silly story about prime numbers helps to illustrate where the Ontological Argument goes wrong and why this way of thinking just doesn’t work. I guess I may slightly differ from Hume and Kant in that I have no problem with necessary beings or necessary existence as long as those beings are not in causal contact with every possible world. Abstract objects can exist necessarily (mathematical realism). Possible worlds themselves can exist necessarily (modal realism). But nothing can be a part of every possible world.

A beneficent, all-knowing God is an automaton. He has no free will, cos in every situation He is constrained to make the best choice. If two options seem equally good He must evalutate them to more decimal places.

He must also be incredibly bored, knowing exactly what will happen for every chronon of infinity.

I've always liked something about the view that every world which is logically possible is also metaphysically possible. I think this is what you are saying when you say:

"As long as a purportedly possible world contains no internal contradictions, then that world seems to be possible."

I have heard many counterexamples to this view, however. There is Kripke's famous example of water not being H20; he says this is logically possible but not metaphysically possible. Souls might be another counterexample - if you have a certain metaphysics then they are logically possible but metaphysically impossible. I've also had the idea of a world with a necessarily existing unicorn. If we accept the S5-style axiom that "whatever is possibly necessary is necessary", then a world with a necessarily existing unicorn is logically possible but metaphysically impossible. If there were a single metaphysically possible world with a necessarily existing unicorn, then the unicorn would actually exist, so such a world is logically possible but not metaphysically possible. I'm curious what you think about these types of examples. How would you respond to someone who thinks there are logically possible worlds that are not metaphysically possible?

Also, great post!